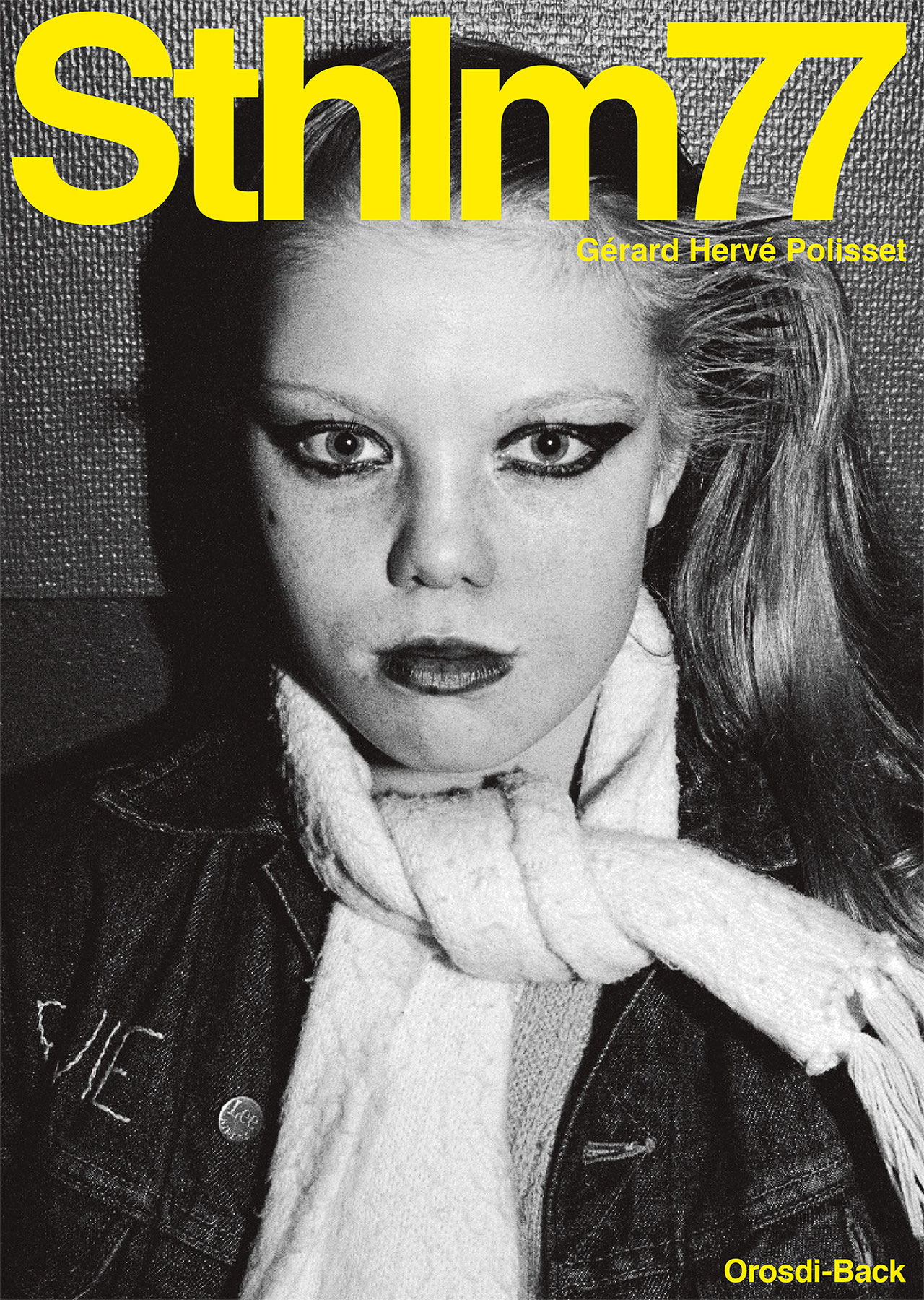

Gérard Hervé Polisset’s photo documentary book captures a moment of Stockholm’s 1977 pre-punk scene, with follow-up interviews.

Texts by Håkan Lahger and Claes Britton

“The images are not really of punks but more about what these kids were going through at that time. To them this was punk and rebellion and no one today can take that away from them. It’s that story that makes them relevant today.”

Frederik Lieberath

“Punk’s not dead!

It just aged 30 years”

Vice Magazine

“Fotografierna är närgångna porträtt på individer som just var individer, oskyldigt under det hårda yttre. (…) Här finns en lekfull attityd som vägrar infoga sig i vuxenvärldens tristess.”

Folkbladet 2018

(in Swedish)

“ … earlier that evening we had asked a punk if he knew about Andy Warhol, and he answered, ‘Of course, I know all the dudes who skateboard.’ ”

Anders Grafström, 1978

In 1973, I moved from Paris to Stockholm to study graphic design and photography at Konstfack University. When the year was up, my real education began at Ericson & Co, an advertising agency in Gamla Stan. My colleagues were real characters. We were like a big dysfunctional family without rules or hierarchy. The founder and driving visionary force of the company, Hans Christer “HC” Ericson, taught me everything I know in the trade.

Anders “Graffe” Grafström, from Härnösand, started there almost at the same time as I did. We worked day and night; unwinding at Operabaren bar and Restaurant Victoria in Kungsträdgården. Disco was king, but my taste leaned more toward Roxy Music and rockabilly. Skateboarding had just arrived in Stockholm.

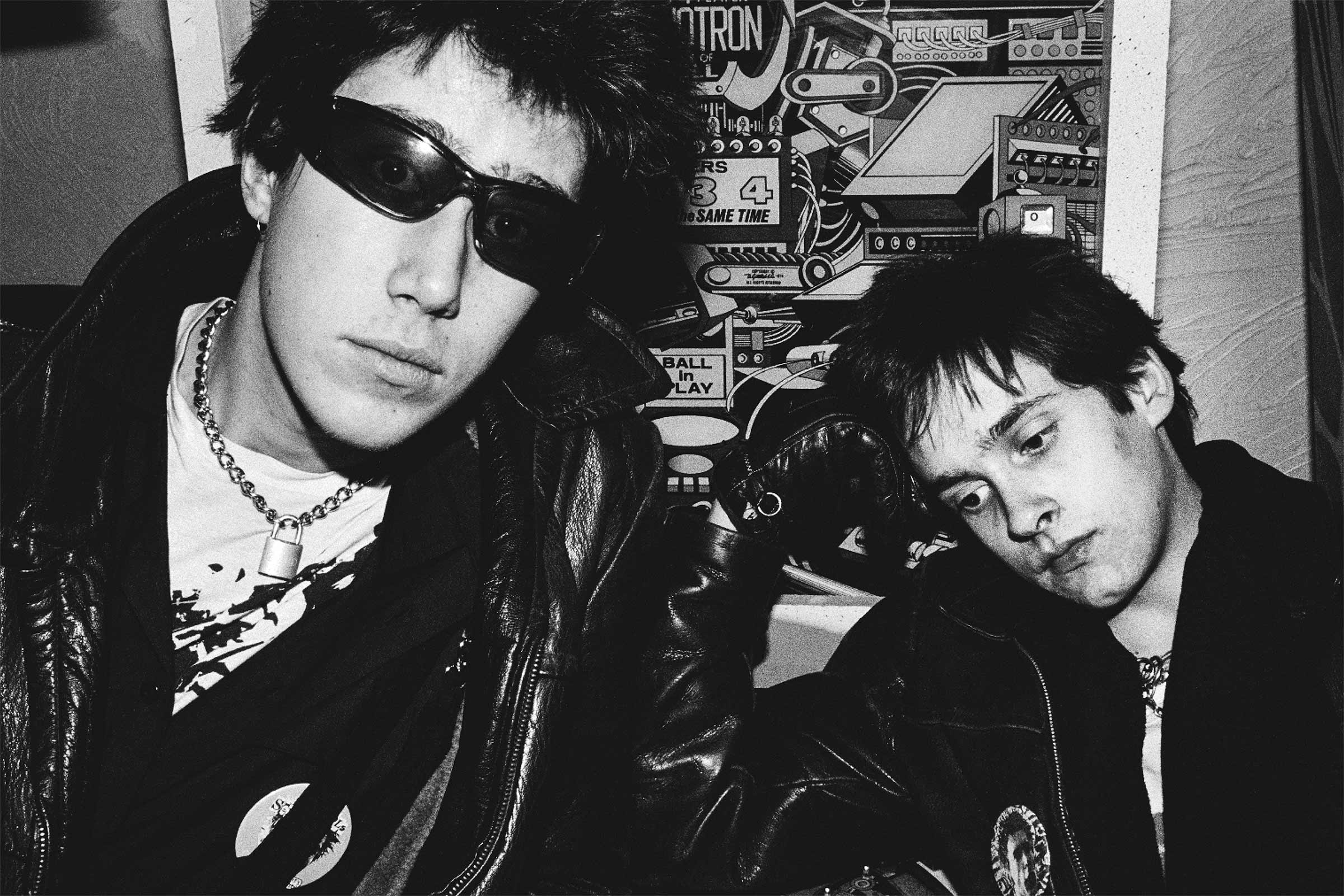

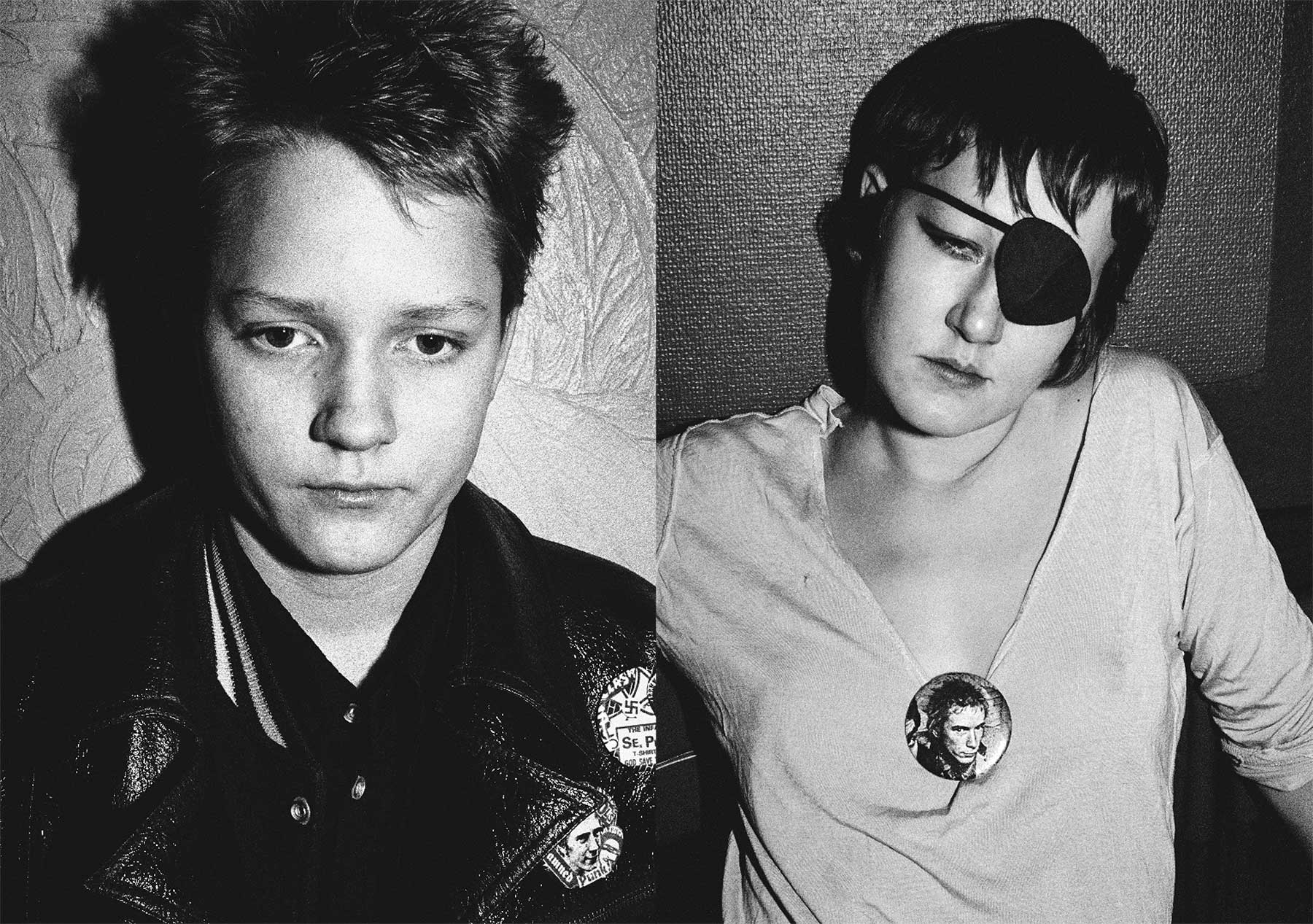

Suddenly in 1977, the punk wave hit Stockholm from London, via Paris and New York. When Graffe and I saw punks around town, we thought they looked so young and innocent beneath their tough exterior. After I came back from a trip to Paris, I told Graffe about a trendy magazine named Façade, and that if we took portraits of the punks in Stockholm, maybe we could get those pictures published by the magazine. After talking to some punks on the street, we were invited to their private parties. We found it all very exciting, so we both began to take pictures of them—Stockholm’s first punks.

Within a month, we had a collection of portraits and showed them to Lars Hall, the Swedish advertising legend who had just started an impressive photo gallery, Camera Obscura, in Gamla Stan. “Thank you for showing the pictures, but what do you want from me?” Lars asked. Our interest in the project died. We moved on to other things. The pictures were stored in a drawer for the next 30 years.

Shortly thereafter, Graffe and his childhood friend from Härnösand, Kent “Loa” Reher, moved to the U.S. While in Florida, they both obtained a private pilot’s license. Graffe then moved to New York’s East Village to become a filmmaker. In 1980, I moved to New York City and on March 23 of that year, Graffe died in a car accident in Mexico. He was 24. Loa found his bliss and became an aerobatic flight instructor, as well as a captain for American Airlines. He died on August 27, 1993 in Florida, at 34 years of age. “Shit happens, as they say in Texas” was one of Loa’s favorite lines. One thing is for sure — life was better and more fun when they were around.

Thirty years later, in 2007, it felt right to revisit that moment in time and place—to find out who and where the people in these portraits were. After I printed some of my photos in a New York lab, I enlisted the help of journalist Håkan Lahger, who was able to locate and interview some of the subjects. I must say that the most interesting part for me was to meet them again.

With its completion, my project has now come full circle. Eric Ericson, the youngest son of my early mentor, HC Ericson, was one of the main motivating forces that brought the project to completion. I see this project as a photo documentary about a small, unique group of very brave youngsters who dared to be pioneers before the punk wave became established in Stockholm.

Gérard Hervé Polisset

“Such was the somewhat ironic faith of punk: Burn fast, die young, beautiful corpse—but surviving eternally in the perpetual commercial circulation of fashion. Let’s say that it’s very well at that.”

Claes Britton

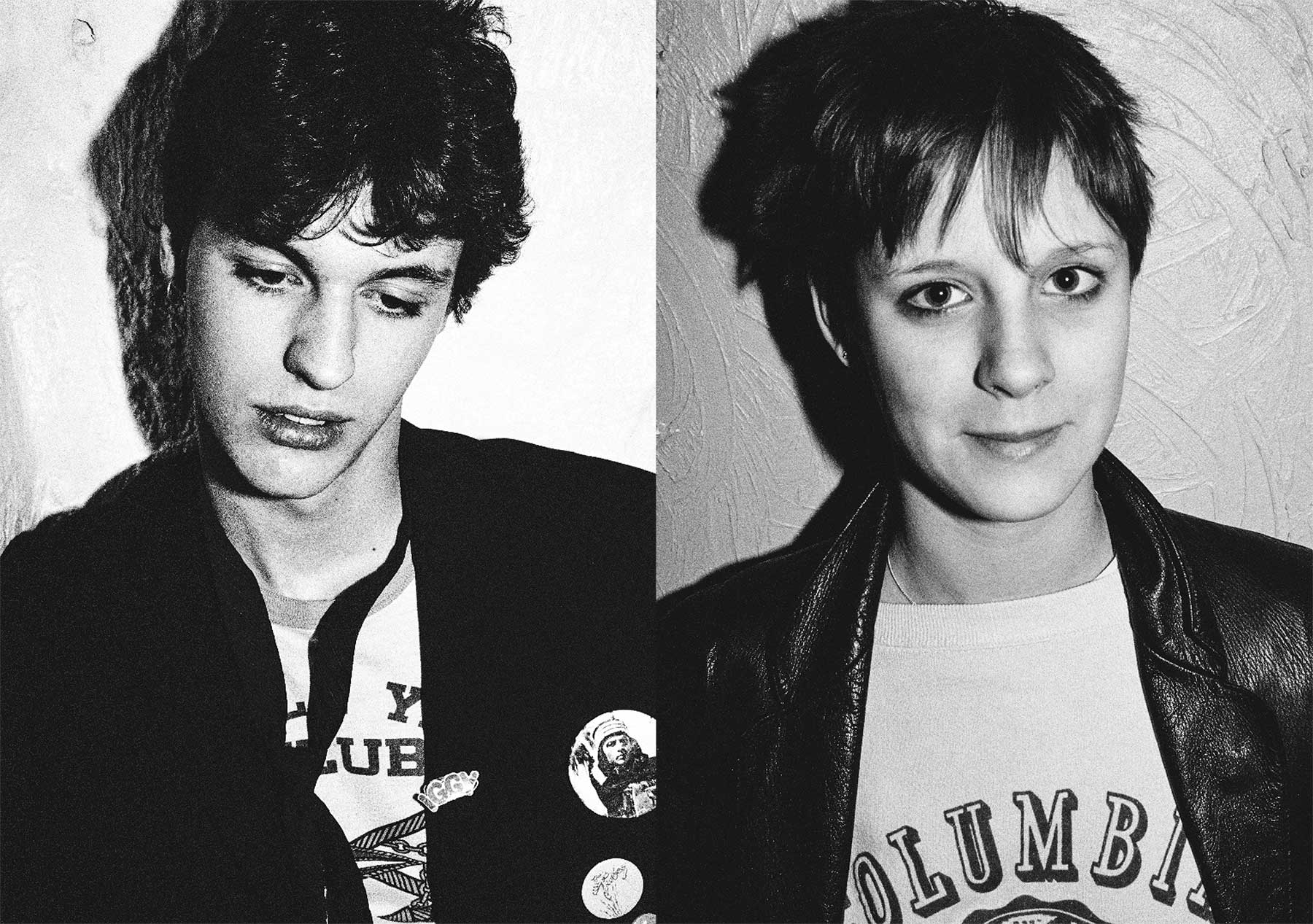

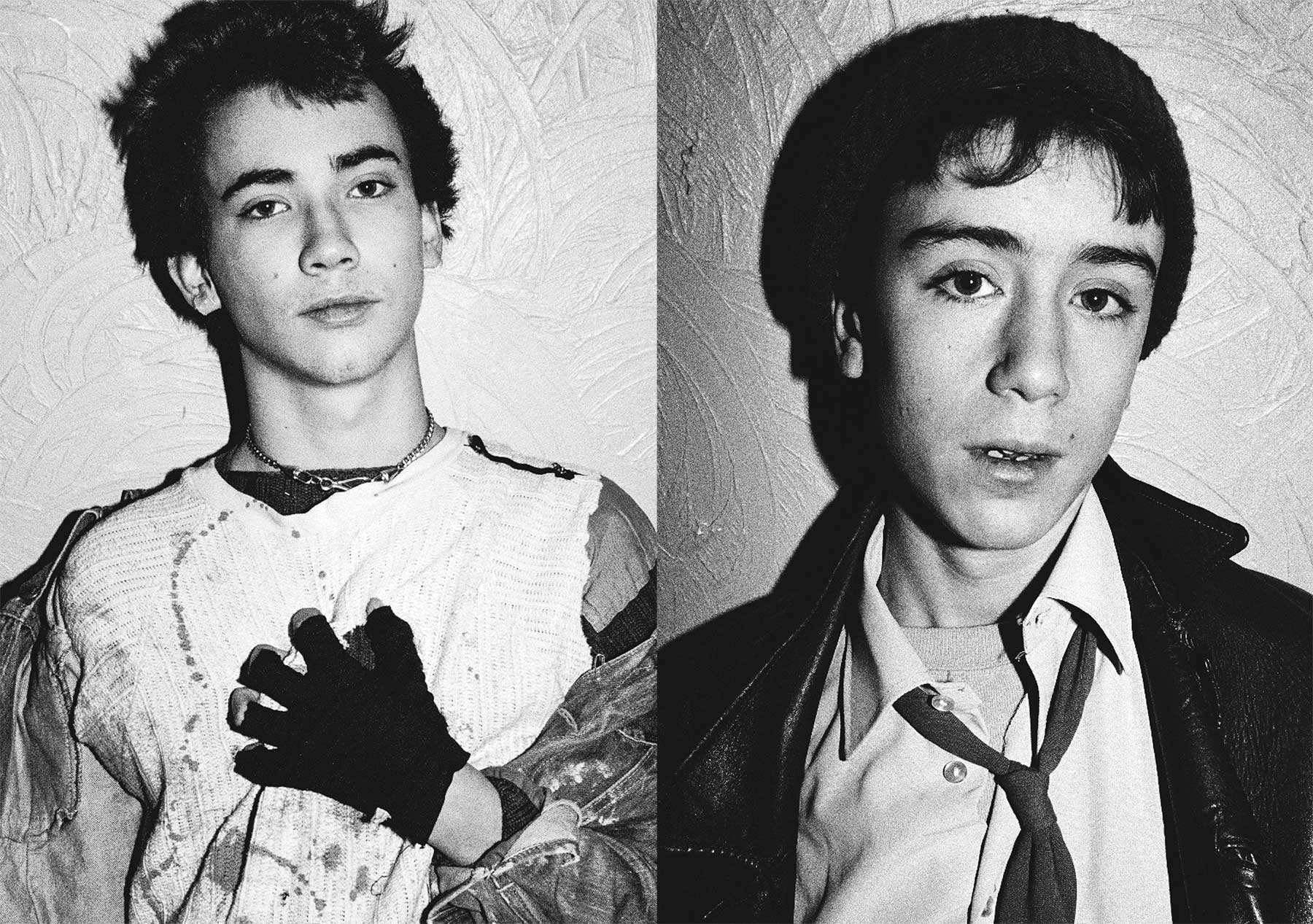

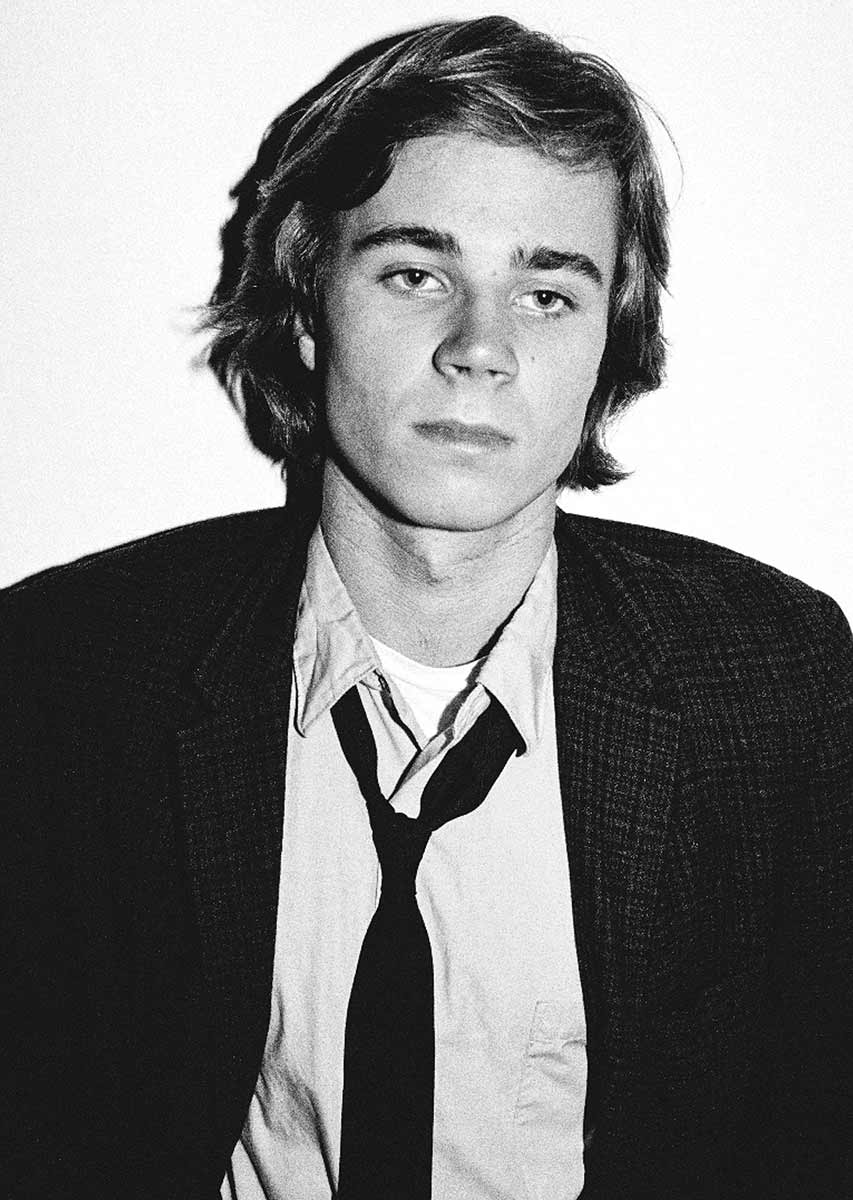

Lars Heikkinen,

age 15

— Lasse, your picture is in the paper, Matilda my niece tells me all excited on the phone.

What kind of picture? I am thinking—hoping it’s not from the Swedish mafia book where I am featured in a story describing my Hells Angels years 1992–99.

— It’s an old punk picture of you, she says cheerfully.

— What sort of punk picture? I ask, relieved.

— It’s of you and some other punks in a magazine and there is a web link–www.sthlm77.com–go and check it out, she says.

— Okay, I reply and hang up.

I enter the web address on my computer and the first picture I see is of Eva. For a moment I am closing my eyes to collect my thoughts. Thirty years ago but it feels like yesterday. Feelings are rushing inside me and I am overtaken by longing, the longing back, back to Stockholm ’76–’77. Somewhere in this haze of feelings I see the pictures popping up on my computer screen, Punk-Linda, Pelle, Jannis and the others. (…)

I will never forget when punk came. We listened to a tape and looked at pictures of Sex Pistols who started a revolt against everything and everyone in England. Then and there, punk started for me. We cut our hair, pushed safety pins into our cheeks, smacked each others’ noses to bloody our T-shirts. Totally crazy but that was what we had been waiting for, our generation’s liberation, and it came in a rush, you just had to hang on. In the beginning it was not so much about the clothes but rather about the music, it was the answer to our frustrations, it gave us a feeling of total freedom. We recognized punk, we embraced it, we were immortal there and then. In a very short time, punk exploded in Stockholm’s suburbs with band rehearsals and performances in everyone’s cellars. I hung out with Eva, Punk-Linda, Sussie, Micke Selder, Jannis, Grassman, Thomas Biström, Jonas Sjöberg, Criss, Catta, Pelle, Linda Roberts, Miko, Hassan, Cheriffen, Robban, Petra, Stejmo, Nettan, Lasse Ralf, Anders Westerberg, Tvillingarna, etc, etc. Everyone knew everybody during the first wave of ’77.

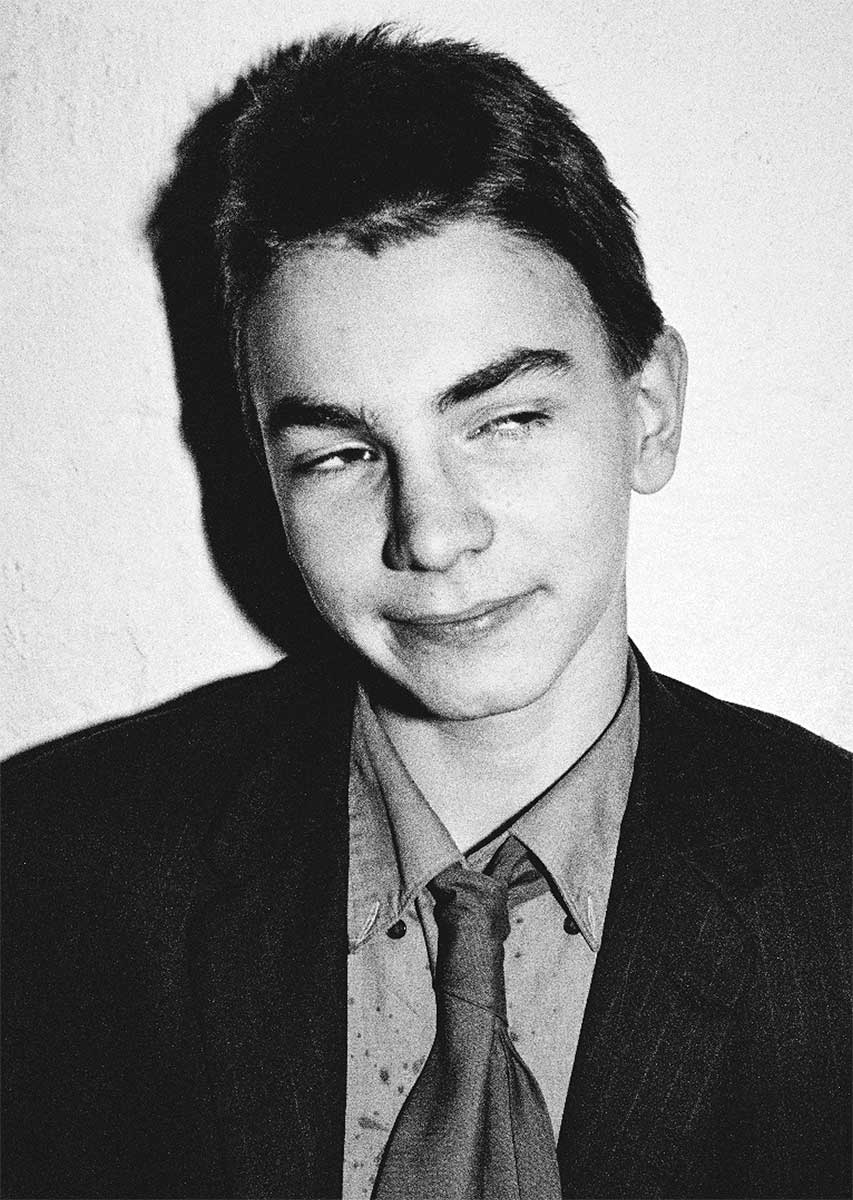

Jannis Östlund,

age 15

I’m still a punk at heart! When Gérard contacted me with questions about that time, my first thought was, “That’s none of your fucking business!”

But like the middle-aged person that I am now, I quickly came to my senses and tried to remember. When I look at the photos, I’m struck by how young we all were. Just kids. I look so vulnerable but I remember how I felt invincible.

I have a hard time remembering long sequences from that period. I remember we spent so much time in the subway. We were always on our way somewhere. Always had things going on. Going to parties. Sneaking into shows at Gröna Lund. Meeting girls. Scoring hash. Drinking beer. Meeting girls. Sleeping over at someone’s place. Heading to a party on the other side of town. Stopping by at home only for a quick shower and a change of clothes. Meeting girls. Going to shows. Altering our clothes to make them more punk. Showing up at school now and then, as well.

I had a “bromance” with Lasse Heikkinen [also in the book]. Lasse was totally charming, friendly and fearless. We met at a teen center. We were both into pop music, had bangs down to our chins, but when we heard Anarchy in the U.K. that was it. We cut off all our hair in the most uneven chunks we could, tore up our shirts, scrawled letters in white paint on our baseball jackets. This new, wild fashion and music style looked and sounded exactly how we felt: “We’re not like the rest of you!”

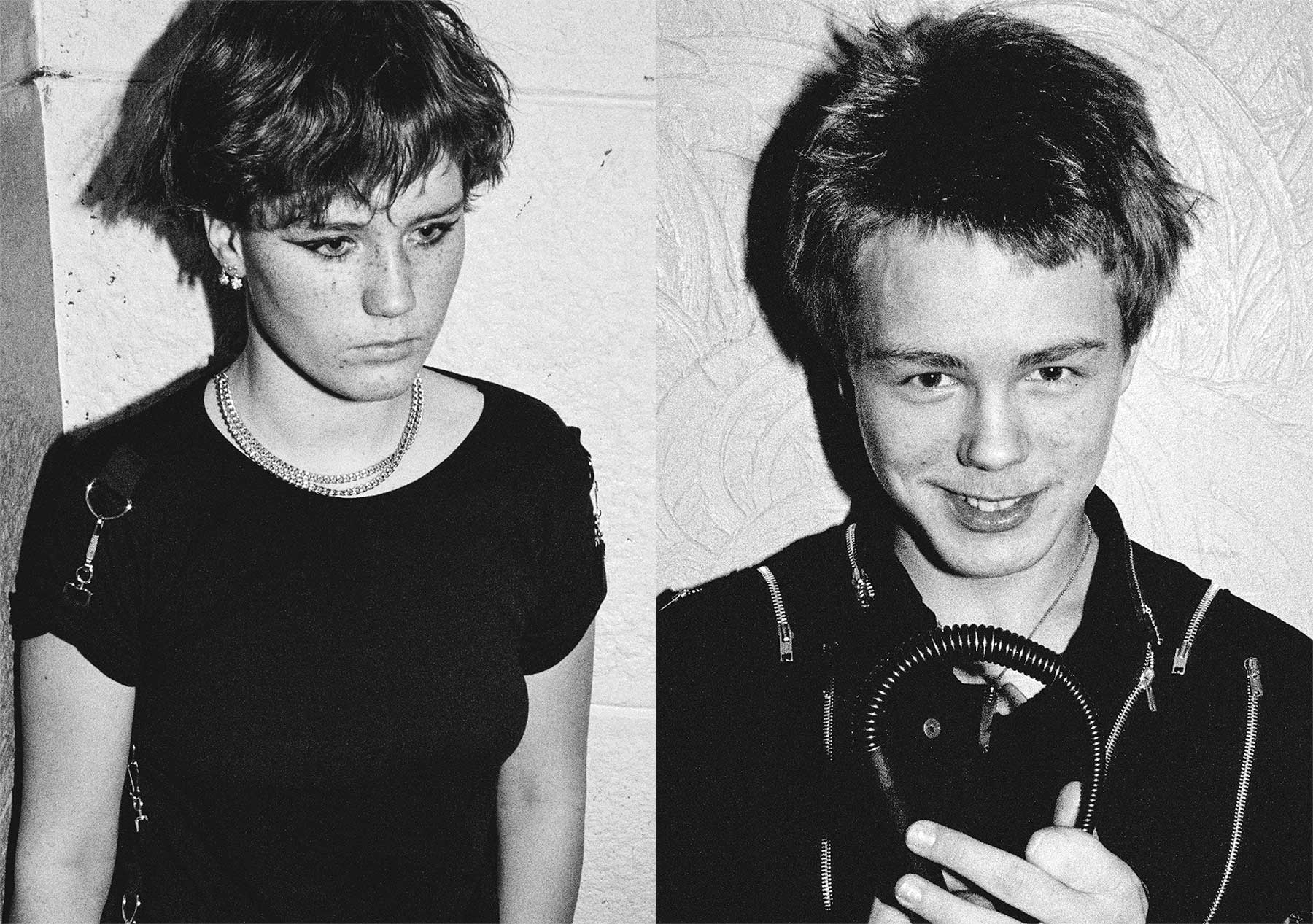

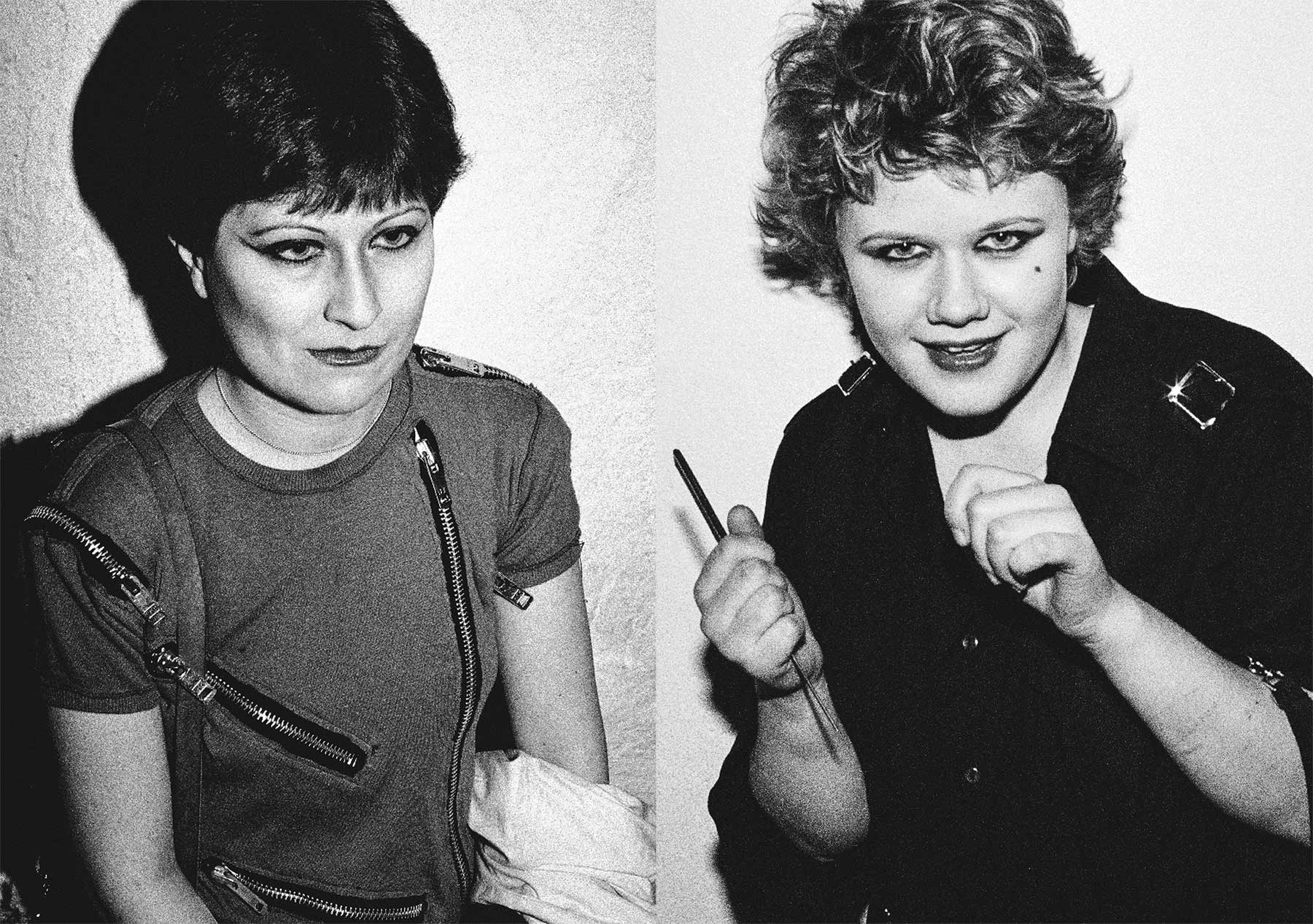

Marie Spagnolatti,

age 16

“A good thing about punk was the way it made room for the girls who were into it, more room than they were otherwise allowed. Also, girls turning toward punk were pretty tough and didn’t follow the traditional feminine model of pleasing men and stuff like that. There were girls who partied, made a lot of noise, caused a scene. Today I can clearly see how those girls within this sphere didn’t end up as traditional housewives or choose traditionally feminine occupations. They chose other careers. I don’t know if they would have done it otherwise, but this movement worked for us anyway, it fit the kind of girls we were.

Part of the reason we were able to go out and get streetwise was likely because we looked like deviants, because you have to put up with a lot if you appear to be different. We learned to stand up for ourselves, especially us girls. And that’s what I have kept as a positive experience from that time.”

Yvette Häggqvist,

age 16

“Punk taught me to be myself. To feel included in a group of outcasts. To dare to break the rules. I wouldn’t have wanted to miss out on that. But if I found out my daughter had done the kinds of things I did, I would die! I didn’t get involved in it for political reasons, my best friend had tickets to a Pistols concert (which was later canceled). I guess you could have called me a “wannabe punk,” but thanks to punk I was exposed to political opinions that I still believe in.”

About the book

In 1977, Gérard Hervé Polisset wandered out at night into Stockholm’s underground scene to document what happened to be the first punk wave in Sweden. This book features around 60 of G. H. Polisset’s portraits from that year.

The music journalist Håkan Lahger was commissioned to find the people in the photographs thirty years later, to ask them about their experience from 1977 and why they joined the punk wave. Some were not alive anymore, but most could be reached to tell their stories. Some of them became today’s famous faces in Sweden’s cultural circles. Anders Grafström, Lena Endre and Olle Ljungström are some of the contributors.

This large format book showcases G. H. Polisset’s photographs as well as texts in Swedish and English by Håkan Lahger and Claes Britton.

Pages: 104

Size: 27 cm x 38 cm

Printing: Duotone

Weight: 978 g

ISBN 978-91-8862-928-9

As of February 2021 Sthlm77 is now distributed

by Stjarndistribution AB Stockholm Sweden

www.sdist.se, email order@sdist.se

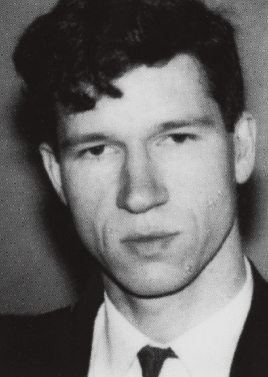

Gérard Hervé Polisset

Gérard Hervé Polisset grew up in Paris where he studied graphic design and photography at the École Supérieure d’Arts Graphiques. He moved to Stockholm in 1973 to attend a one-year special program at Konstfack. He subsequently worked at Ericson & Co and Brindfors advertising agencies. In 1980, he moved to New York City where he continued working in design and advertising. He is currently working on private projects from his home base in Florida. Photo from 1977.

Contact

Exhibition

14 Pigment Prints size 74 x 110 cm printed 2018 by Prodig AB, Epson Premium Semigloss photopaper (250), unmounted, unframed.

3 Pigment Prints size 110 x 140 cm printed 2018 by Prodig AB, Epson Premium Semigloss photopaper (250), unmounted, unframed.

9 Photo Prints size 70 x 100 cm printed 2007 by Förstoringsateljen AB, mounted on aluminum

plate.

75 Photo Prints size 40,6 x 50,8 cm printed 2000 by author, unmounted.

Please contact Gérard Hervé Polisset for more information.

Thank you

My book is dedicated to Anders “Graffe” Grafström (1956–1980). Thank you to all the people I photographed 40 years ago in Stockholm. After all this time, it feels more like I am looking at faces of family and old friends. This is your story, your book.

/ Gérard